FCKG Windows Activation

When people would ask me what it was like working on Windows, I would sometimes say, “It’s like a church potluck. You bring a dessert, another team brings macaroni and cheese, and another team brings the tomato aspic.” Even though nobody ever asked for tomato aspic.

When I joined the setup team in Windows in Oct. 2000, I didn’t know exactly what my role would be day to day, just that I’d been hired in as a program manager to focus on “corporate deployment”. Windows is weird, because for the client at least, there are always three audiences you have to think about as you are building a new release of the product:

- OEMs (original equipment manufacturers) who design and manufacture personal computers (your Dell, HP, IBM back in the day, etc.)

- Enterprise/business customers, as well as education, non-profits, etc.

- Retail customers, who would buy the full packaged product off of store shelves (remember, this is 2001).

Those three were the priorities, very much in order for Windows XP.

First was the OEMs and new computer sales. Almost all of my peers and my manager were focused on OEM customers, as that’s where Microsoft—at least then—made a good percentage of revenue, and XP was chartered with helping, which was especially important given how Windows ME had gone.

Second priority was enterprises, where Microsoft was doing well, and where Windows XP would do phenomenally well, once business customers got over the “Fisher Price” theme of Windows XP, as one corp customer called it.

Third was retail upgraders (or people buying Windows to go along with a newly built PC), particularly important since Windows XP itself was focused first on home users, even though it was, at it’s core, an updated (one can argue philosophically whether it was or was not “improved”) release of Windows 2000, plus a new edition (Home edition, briefly called “Personal” during the development of Windows XP) that would sell for the same price point that Windows 9X had sold at forever, with a feature set that had been intentionally pared back to work better (or at least more efficiently) in home environments, where these machines would stand alone, never being joined to Active Directory, and often not having a reliable or always on Internet connection, or IT team to support it. The one thing about XP you have to remember is, we had a good-sized team, but the one thing we did not have a lot of… was time.

You have to remember a few things here, as this was 2000, headed into 2001. It’s important to set the stage:

- Windows 2000 would release to manufacturing in Dec. 1999, and become generally available in Feb. 2000. This release would be almost entirely focused on business customers.

- Windows ME would release to manufacturing in June, 2000, and become generally available in Sept. 2000. This release would be almost entirely focused on OEMs (to sell more computers).

- Windows XP (code-named “Whistler” during development) would release to manufacturing in Aug. 2001, and become generally available in Oct. 2001. This release would be focused on consumers, in terms of helping OEMs sell new computers, and convincing people to upgrade their existing Windows 9X PCs to XP.

I could talk for days about those three points alone, but that wasn’t why I sat down to write this today – maybe another time.

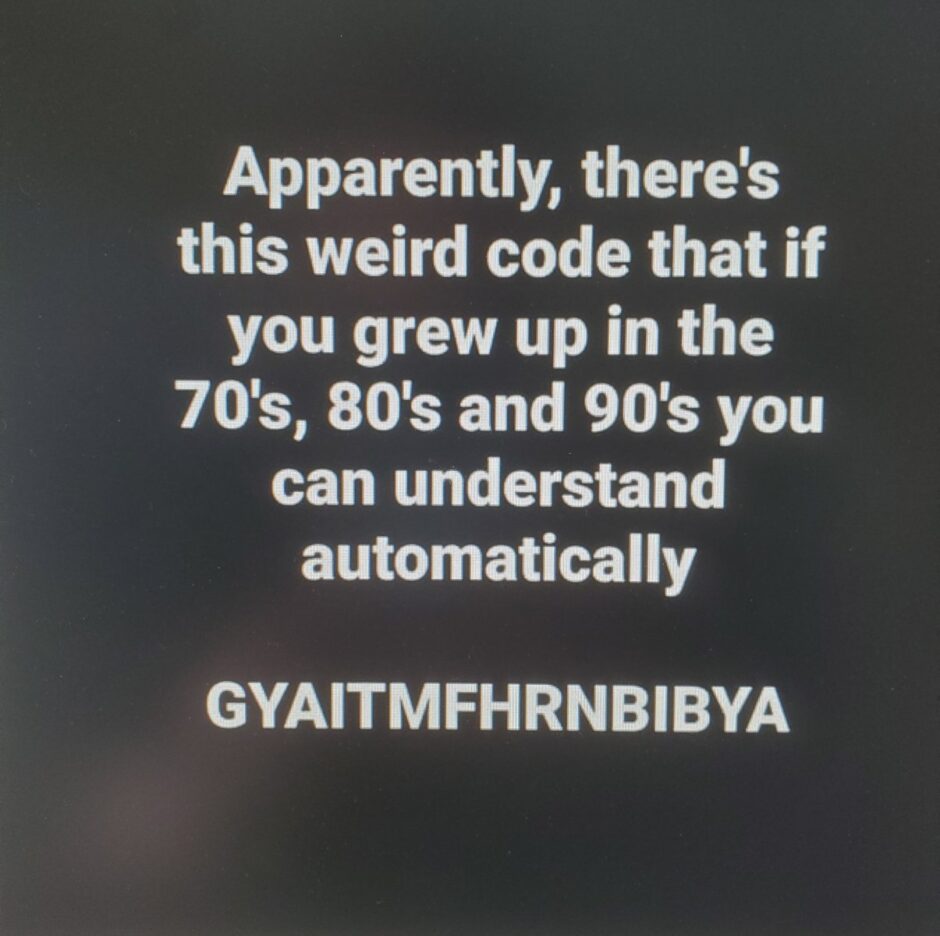

No, last week, I saw the meme below fly by and it made me laugh.

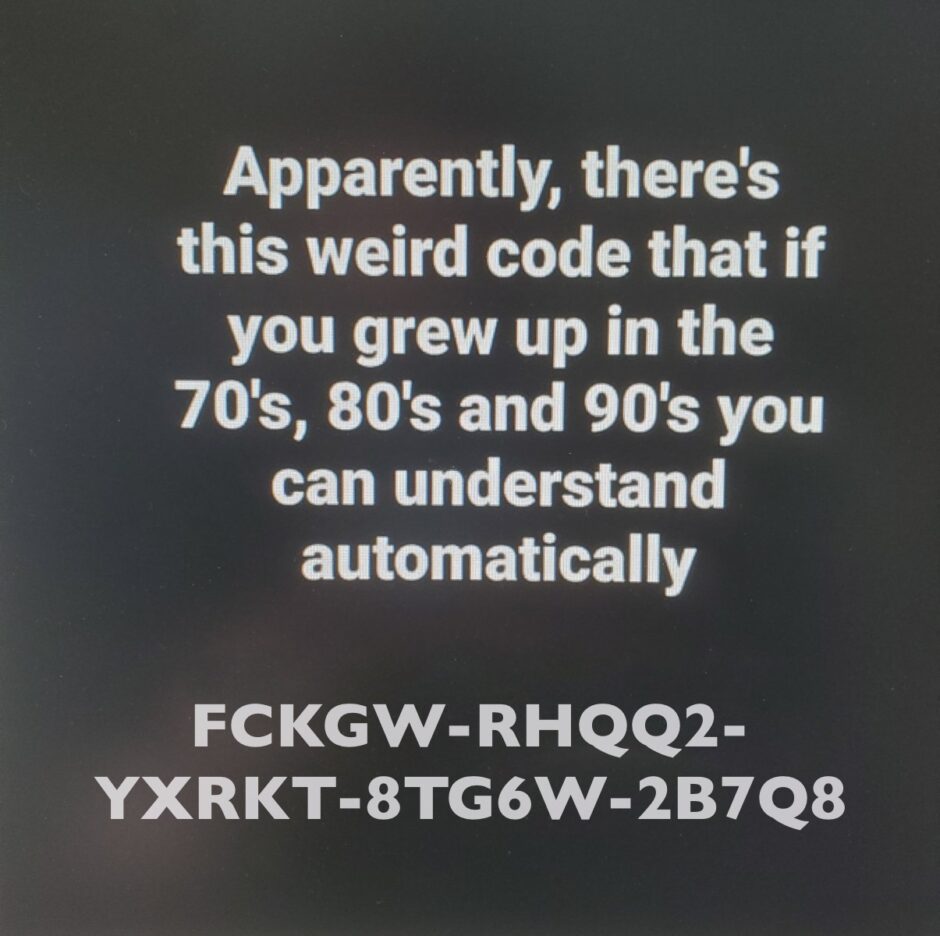

So I thought to myself, “I wonder if people would think it was funny if I changed it to be the well-known Windows XP product key.”

So I fired up Pixelmator (love that app) on my iPhone, erased the bottom of the image and added the product key.

I figured a few dozen people might get a laugh out of it. It turned out to resonate with a few more people than that. (By the way, I always read the first part of that key out loud, hence the title of this post.)

Windows XP would be the first release of Windows that would have activation (along with the Office sibling release). Rather than taking a specific range of basic product keys forever, Windows XP would validate the product key with Microsoft over the Internet where available, and the phone where the Internet was not yet ubiquitous. (And in general, it would work, though prove rather unpopular with some.)

The goal wasn’t ever to completely eliminate piracy, but to reduce casual piracy. Prior to activation, Microsoft product teams each had different approaches to trying to reduce piracy, which typically involved a range of product keys. (As many know, a lot of older Microsoft products had very simple product key checks, and in many cases had special bypass sequences that reveal replies to my tweet mentioned.)

I didn’t know, when I started in Windows, about the tomato aspic. But I’d argue that for those of us on the Windows setup team, the Windows Activation team brought the tomato aspic. At least that’s how we felt when we’d eventually go talk to customers and had to explain the intricacies of Windows Activation and product keys. (I want to add a caveat here that the team that built activation was a great group of smart people that I really enjoyed working with, regardless of how cynical this post may sound.)

So when we look at those three customer segments above, Windows XP had different behavior for each of them:

- Big OEMs did work so that Windows XP would recognize the hardware it was on, and activate automatically

- Retail customers would receive a box with a product key that they could activate over the Internet or the phone

- Enterprise customers… would get a pass for Windows XP – there wouldn’t be activation.

That is, business that licensed Windows through what is called “volume licensing” (VL) would receive a release of Windows that had two key (pun not intended) differences between retail or OEM, which always wanted to be activated. VL media (the releases of Windows that went to businesses) would require a product key that looked, fundamentally, the same as a retail/OEM key, and would check that key when it was provided, but wouldn’t enforce activation in the same way that retail or OEM did with consumers. (This was typically referred to as a “VL key” or VLK.)

Why wasn’t there any activation for business customers? I wasn’t on that team, they were elsewhere in the company. While several colleagues worked with them (since activation and Windows OS setup were so intertwined), I only had a little bit of communication with a program manager and a developer on that team prior to XP releasing.

I believe that the absence of activation for businesses came down to time. The team building the infrastructure didn’t have the time to build out a proper activation system that would work for businesses (something they already had ideas for before XP shipped in 2001). So instead of building something hacky, they waited and the right thing was released when Vista shipped many, many, many years later.

In terms of taking care of their VLKs, I can’t speak to how it was communicated to business customers, but I know they were told something like “This is your organization’s product key. It is very valuable. Please try to protect it.” (It was likely a more stern warning, but I have no idea.)

All I know is that what probably became the most famous product key in history, the XP VLK that starts with “FCKGW” leaked after we had shipped the OS in Aug. 2001, but before general availability in October. That tells you a little bit about how it leaked, and from where – there weren’t many customers who had their own VLK in hand by that point… let’s just say it probably leaked from a company that made hardware.

In hindsight, someone within Microsoft should have also started a pool about when the first VLK would leak. But honestly I don’t think any of us could have guessed it would have happened that rapidly, let alone how well-known that one key would become.

Much like local administrator passwords in an unattended setup file, there wasn’t a whole lot that could be done to protect a product key, since it sat there in clear text. As we were working on Service Pack 1 for XP, I sat down with one of the setup UI developers and we talked out a design for protecting product keys for customers who wanted to try and protect their VLKs from compromise.

A simple set of switches were added to winnt32.exe, the setup executable for most NT-based Windows releases prior to Vista. These would let you encrypt (but not decrypt) your VLK for 5-60 days, and it could be run quietly. The design thinking here was that you could write a script that would automatically update the encrypt the product key on your file servers or Remote Installation Services (RIS) servers where the OS was deployed from, using a scheduled task.

The VLK then would be protected from prying eyes looking to rip it out of an unattended setup file or other answer file used by Windows setup.

The decryption code was added to the unattended setup file processing logic within winnt32 so that the key would be transparently decrypted and applied to the resulting installs of Windows XP. End users didn’t have to do anything.

It wasn’t perfect, but it gave customers something they could do to protect the VLK if they were willing to. I have no idea how many customers used it, but I think even offering the option was worth the effort.

Ironically, that one product key (which Microsoft would take some efforts to try and stop the use/abuse of) would last forever, and be abused as long as possible.

I mean here it is almost 23 years after XP released to manufacturing, and just three days after I posted it the tweet has over 2M impressions, 8,500 likes, and 1,000 RTs, and over 600 replies.

It’s kind of amusing that a product key would have this much cultural significance, and be easily recognized by so many, and generate some good laughs almost a quarter of a century later.